I grew up–while not in open fields, farmland nor forests–in a fairly nature-based childhood nestled within the relatively safe confines of the suburbs. My childhood was predominantly in Columbia, Maryland, in the ’70s, with its miles and miles of pathways, creeks aplenty and many thin slivers of woods abutted by housing developments and neighborhoods all around.

Like many somewhat-feral children of the ’70s, we were encouraged to play outside, be outside, and basically not be in our parents’ hair as much as possible. (I’m guessing that was probably a two-way street of mutual interest for most of us kids.) Life in Columbia made playing outside easy, as every single kid lived within a short walk of a path, which inevitably led to a creek, or a thin stretch of woods, or some place outdoors and (mostly) out of sight of neighboring and nearby adults.

In addition to that backdrop, my mother was on the “natural” side of the spectrum, with a vegetable garden in the backyard, a bunch of berry plants around the quarter-acre yard (strawberries, blueberries, blackberries, raspberries–both red and yellow, and even gooseberries, if you’ve ever had those), and a heroic attempt at fruit trees (peach, apple, cherry, plum and maybe even another one or two that slips my mind … oh, figs, too!).

She canned tomatoes in high summer, took us strawberry and cherry picking at nearby orchards (Sewell’s Orchard neighborhood was an actual fruit orchard before it was a housing development) and enrolled our help when making jams and jellies with the fruit we’d picked.

We composted all our produce and vegetable scraps, turned the compost throughout the year to mix it well, and harvested the nutrient- and microbial-rich soil each spring to add to the garden.

We were, in many ways, invited to step into the world of nature as playground, teacher and companion.

a find!

I remember being quite fascinated by praying mantis as my knowledge about nature and bugs and life and death increased. They were big bugs, comparatively; they were bug-eating carnivores ,and quite useful in the garden; and I was both horrified and fascinated upon discovering females were prone to decapitating (and sometimes eating) their mates. Plus, their egg cases were so interesting, so distinct and so coveted. A praying mantis egg case meant praying mantis babies; and babies meant future adult bug killers galore, and that was a good thing.

So, you can imagine my delight when I discovered a praying mantis egg case one day out in the fields near our house. I broke off the plant stalk it was connected to, brought it home, put it in a brown paper bag and decided I would keep it until spring when the babies would hatch. What a bonanza of bugs we would have! How helpful I was being!

So, you can imagine my delight when I discovered a praying mantis egg case one day out in the fields near our house. I broke off the plant stalk it was connected to, brought it home, put it in a brown paper bag and decided I would keep it until spring when the babies would hatch. What a bonanza of bugs we would have! How helpful I was being!

I think I was nine when I made this discovery and brought my bug bounty back home.

Another thing I discovered when I was nine and in the possession of said praying mantis egg case was bugs respond differently when in a nice heated home than they do when outside and subjected to the traversing of the earth around the sun, the vagaries of seasons and the cooling, then warming, of the earth and air.

Yes, there was a day–it was in late fall, I think–when I started to see dozens of tiny little praying mantis babies crawling all about my room, searching for food and water, neither of which my nine-year-old’s room provided much of for them.

I scrambled to catch them all but knew–even in catching them–they had no fate but death ahead, for we couldn’t keep them in the house, and they would die outside in the cold-and-only-getting-colder weather.

It was an innocent mistake, a child’s mistake, a mistake of ignorance and not knowing. I knew that. I understood that. I also felt bad that I had needlessly caused their deaths and had interfered with their life cycles. It was also a lesson about not messing with nature–letting it be what it needs to be, on its time table and its trajectory.

Nature can be a teacher; this was, most certainly, a teaching moment.

the bird that never flew

I had a similar-ish experience decades later when I was outside one day and saw a fledgling bird on the ground; its parents above, flying around and squawking at me as I got close to their fallen baby.

I figured the thing had “fallen” and was going to die, so I took it home; found out from someone or some source that I could soak some dry cat food in water and try to feed it to the baby with a dropper. I think I suffocated the baby by accidentally getting food into its nostrils. Or maybe I choked it by not making the food mushy a bit. Or maybe it died from being the wrong temperature. Or the stress of being taken from its parents. I don’t know. It didn’t make it 24 hours in my care.

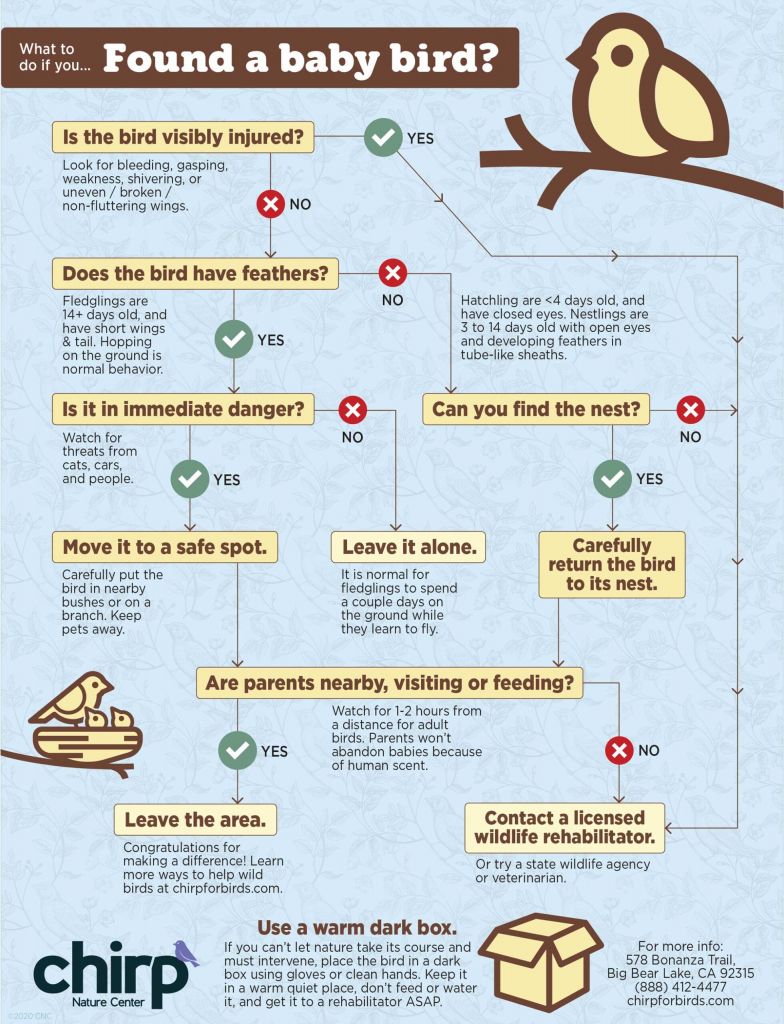

That’s when I learned–after the fact–you’re supposed to leave baby birds with some feather development (and eyes opened) alone. Sometimes their parents push them out of the nest to get them to fly. Erg. Didn’t know that. Now I do. Here are some tips for responding to baby birds found. Live and learn.

Side story: Did you know praying mantis are fond of eating hummingbirds? Apparently they like their brains the best.

Mantis on snail photo by Nordin Seruyan.

1 Comment

David Hobel Thompson

I miss praying Mantis’s. I saw them all the time growing up in Columbia, MD. We don’t have them here in Illinois.